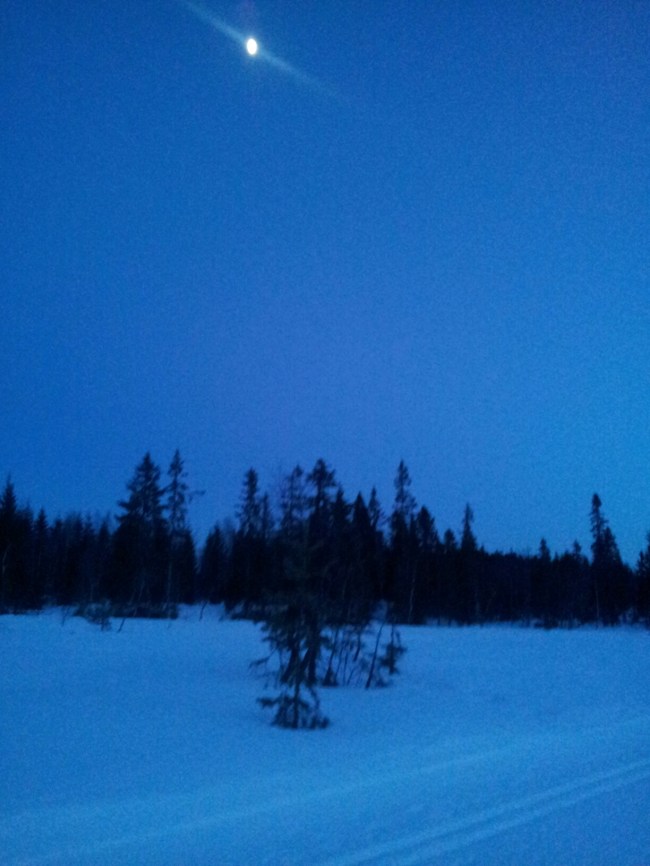

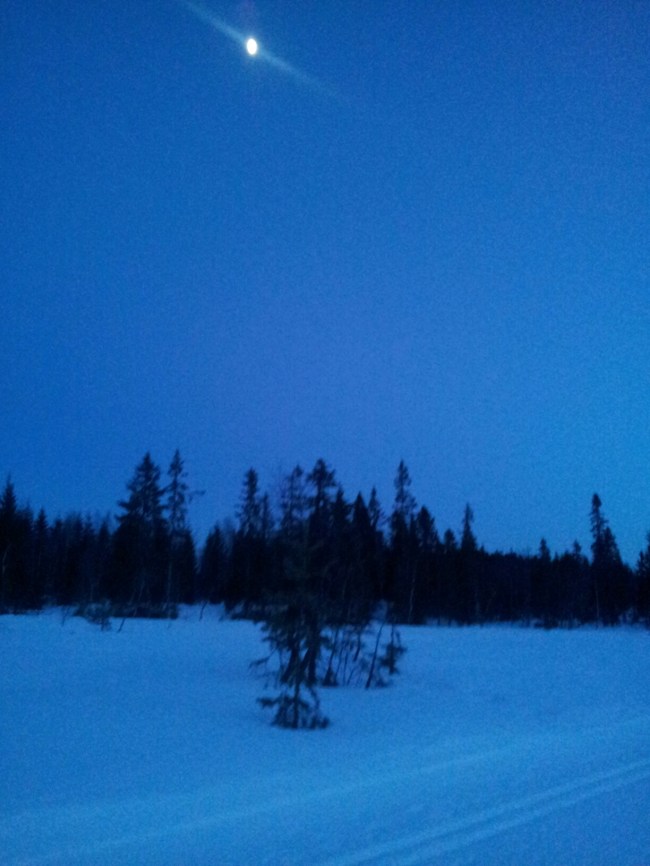

Schoutbynacht has been xc-skiing tonight. Actually, the picture was taken a few days ago, so tonight the moon was even larger. No need to light the headlight, which broke anyway when I had a drink of water and ripped the cord.

This year spring is late in Norway, and so the snow is amazing for this time of year – dry powder. Normally by now it would be all crystallised by the constant oscillation between daytime sunshine and nights with minus five, six, ten. Instead, the snow is still dry and quite clean, not full of pine needles and bark. So conditions are great for classic style XC using normal wax – blue extra, for instance. Plenty of grip.

So I got out and hit the snow at 8pm when the last daylight was receding – just a faint stripe over the treetops to the north west. One other car in the car-park, and over one hour and forty minutes I saw two people, none of whom returned my greeting, and one dog, which barked with a certain amount of enthusiasm and no ill intent from what I could see. No moose, either, though I must say I was on the look-out. There are plenty in the woods here, I have met them twice, and while they are generally no trouble, they are HUGE, and if they decide to go for you, you better get outta there. So, no elk tonight. Just quiet trees and moonlight filtering down. Makes for a slightly spooky atmosphere, one you can break or spoil by lighting the super mega LED-light that you have on your head. But I didn´t, preferring to go by moonlight. This also sharpens, and by a lot, your sensation of skiing. Your perceptions shift from sight to balance, you start to feel what the body is doing, the pressure of your feet in the shoes, your position on the skis, the jolt transmitted back up your body as you kick the ski down. The smell of pine trees and snow. You get closer to nature. The root of a fallen tree with snow on it towers up ahead looking like a human shape. A shiver runs down your spine. Then you see the moss, the tiny roots, the shape changes into a tree-root shape. Small wonder trolls are popular in Norway. The forest is full of them.

Speed is also higher in the dark. It´s not really, but it feels it, which is more satisfying. Speed, the sensation of speed, is central to skiing. That, and the feeling of power and control. Power, as you thrust yourself forward on the slippery surface; control when you zoom down a slope at speeds exceeding 40 km/h on thin skis and manage to stay upright, clear the curve that comes up ahead, and make it through until things quieten down, the slope decreases, wow, made it!

My plan was to make it to Mikkelsbånn, but I don´t really know where that is, so I turned back when I thought I had come far enough. I drank some water, listened to a plane receding into the distance, verified that the headlight wire was beyond immediate repair, then set course for home, and discovered that it was almost all downhill and a fair bit quicker than coming up.

And I started to think how skiing is a constant element in my life. I remember my skis like I remember my bikes, with the exception of my first skis. There is the photo where I am 4-5 years old, on skis. Those I don´t remember. But the next pair, wooden, Åsnes, with a big Å on the tip – yes. The sole had to be made impermeable by smearing it with a tar-like substance, much like boats in the old days. Failing that, in wet conditions they would ice up like nobody´s business. This tar was also quite flammable, and I have this picture in my head of a common occurrence: when applying sticky wax for icy snow – klister – people would sometimes use a gas flame to heat the damn stuff and make it more malleable, and inevitably all the chemicals would catch fire. Nice blue flames until they petered out on their own accord.

The next image that presents itself is of my Åsnes skis being loaded onto the train in Bergen. How we got to the train station I cannot remember. With my dad it was often a case of being somewhat late – but in any case, the skis were surrendered to the cargo handlers, and equipped with labels. I remember paper stickers that were moistened and attached to the skis, stating the destination, and cardboard labels with a metal-reinforced hole where a steel wire was inserted in order to attach it to the skis, the poles, or other items of luggage. The poles! They were made of bamboo! Sounds like the Middle ages, but we´re in the late 70s.

Then we got on the train. The compartment was hot, the chairs were deep and comfy with green, plush upholstery. They swivelled, so you could make everyone face in the direction of travel. You pressed a pedal, and the whole two-seater could be flung through 180 degrees – clack! Clack! Clack! You sank into those chairs, you did not sit on top of them. They were great. And the train pulled out of the station and into the first of a million tunnels dug by grimy-faced rallars all those years ago. Narrow, black, wet tunnels. It seemed a miracle the train fit inside it. But it always did, and we with it.

The trolley came down the aisle, and maybe we got a bottle of Solo. Sticky, sugary, and ultimately nauseating as the train snaked along the mountainside before starting the climb to 1222 meters above sea level. Relief may have come from the water flasks, one of which was available at either end of the car, which by the way, was divided by two central glass doors that divided smokers from non-smokers. The water flask was made of glass, with a narrow neck, and was filled with tepid, lifeless water. Next to it was a stack of wax-paper cups. These were tiny and rather ingenious, having been fashioned from a single circular sheet of wax paper folded into a cup shape. By pulling along the edges you could return the cup to its flat origins, and colour it. Thus passed a half hour. Many more remained until we reached our destination, late in the evening.

We stumbled out of the train, down the steep steps to the platform, snow-covered and lit up by yellow lamps. A cold dry wind would be howling in from some frozen mountain lake, and the train was a sight! The dry snow was like comet´s halo around it at speed, and this snow clung to every nook and cranny, and even to the bare metal, giving the train a heroic appearance. This was no ordinary journey! This was a fight with the elements! At the front, the locomotive had snow all over its plough and the metal grid protecting the nose. The bellows between the cars were all snowed up! Snow everywhere. The train just blasted through, or so it seemed to me, with a mighty mechanical force.

We hurried off the platform, walked the few hundred yards to the hotel, how I longed go get into that warm hotel lobby with its reindeer antlers, reindeer hides, thick slate tiles on the floor, Kvikk Lunsj and Melkesjokolade on display in the reception together with today´s paper from Oslo. Check in, collect the keys to the room. A normal key attached to a huge metal keyring. It was a roughly t-shaped piece of heavy metal – brass? The bar on the T was circular and padded externally by a rubber ring. On the surface of the circle the room number was stamped in black. There was little chance of carrying this key home inadvertently! Each key nestled in its pigeonhole in the reception, and all we had to do was ask for it whenever we needed to go the room to fetch something.

Finally we got to the hotel room with its strange smells of carpet and detergent, its starched white bedclothes, cool to the initial touch, then warm, so warm that sleep came instantly, even if by now we may have been a little bit excited.

And the next day would break with a light breeze, a blue sky, and a few degrees below zero, and we would equip ourselves with a packed lunch and a thermos flask with cocoa and launch ourselves on the newly-prepared tracks that fell away from the hotel down to the frozen lake, traversing it in a straight line like yesterday´s train tracks.